DR. Alonzo H. Kenniebrew Hospital

Introduction

Text-to-speech Audio

Images

Stone Marker of Dr. Kenniebrew's Hospital location.

Backstory and Context

Text-to-speech Audio

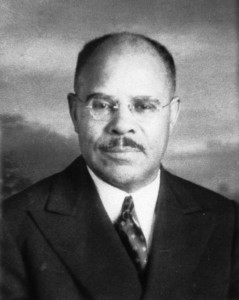

Dr. Alonzo Kenniebrew (physician)

Dr. Alonzo Kenniebrew lived and died in Springfield, and his wife later became one of the most honored Springfieldians of her generation. His most notable achievements as a pioneering African-American physician, however, were accomplished elsewhere.

Kenniebrew (1875-1943) founded the world’s first surgical hospital owned and operated by a Black physician, served as Booker T. Washington’s personal physician, and was close friends with Washington, George Washington Carver and others in the most eminent circles of early 20th-century Black America.

Kenniebrew was born in Shorter, Ala., and went on to graduate from Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, Central Tennessee College and Meharry Medical College, plus post-graduate work at Harvard. He then returned to Tuskegee as the school’s medical director and physiology teacher. Aside from being Washington’s friend and physician, the young Kenniebrew also apparently was Washington’s protégé. Pamela Newkirk wrote in a Columbia University dissertation in 2012 that:

It appears that Washington continued to support Kenniebrew during his medical training. In a letter to Washington dated March 25, 1897, Kenniebrew reported that he passed the medical exam but said he would still look to Washington for financial aid as he completed his hospital residency and a post-graduate course.

Kenniebrew, Newkirk said, “perhaps best embodied Washington’s lofty ambitions for his students and faculty.”

Kenniebrew met his first wife, Lenora (or Leonora) Chapman, an Illinois native who was Tuskegee’s dean of women, at the school.

The couple moved to Jacksonville, Ill., about 1903. However, according to Jessie Mae Schultz Kenniebrew Finley (1906-2006), who worked as Kenniebrew’s bookkeeper and medical stenographer in Jacksonville, Kenniebrew couldn’t get medical privileges at local hospitals. So, in 1909, he opened his own hospital, which eventually became the New Home Sanitarium.

“The original six-room frame building, a surgical hospital and training school for nurses of which he was both founder and surgeon in charge, grew to a modern 67-room three-story building,” the Illinois State Journal reported in its obituary for Kenniebrew.

The facility’s staff was all Black, but an estimated 90 percent of its patients were white. “They didn’t care what color he was because when they got here they were half-dead and he brought them back to life,” Finley told The State Journal-Register in a 1993 interview. None of the graduates of the associated nursing school ever failed a licensing exam, she added.

Alonzo and Lenora Kenniebrew divorced some time after they moved to Illinois. Dr. Kenniebrew suffered a stroke in 1927, which forced him to suspend his hospital work. He hoped to resume his work at New Home after recuperating, but the city of Jacksonville took the property in 1929 to extend a street.

Kenniebrew asked Finley – then the unmarried Jessie Mae Schultz – to move with him to Chicago. Finley described her reaction in a 2003 interview by volunteers for the Springfield African-American History Museum.

And I just sort of proposed to him, and I said, “I’m not going with you anyplace unless we’re married.” So we were married in 1930. And he was thirty years older than me. And he lived – they said he would have had a stroke and die most any time. But … I guess the children added to his life. You know I was married in 1930, he died in 1943. That was thirteen years.

Finley said in the 1993 newspaper interview that Kenniebrew was personally flamboyant, “first driving a carriage with high-steppin’ horses while wearing custom-made white gloves.’” He later drove exotic cars, she said.

“’I may be the only Black woman alive who drived a Marmon (auto),’ she said, laughing at the memory.…”

The Kenniebrews lived from 1930 to 1933 in Evanston, where, in addition to practicing medicine, Kenniebrew published a weekly newspaper, the Evanston Informer. The couple, by then with two children, came to Springfield in 1933, and Kenniebrew opened a medical office in the 700 block of East Washington Street. The office later moved to the 1700 block of East Jackson Street.

Kenniebrew also began a weekly newspaper, the Illinois State Informer, in Springfield in the mid-1930s. Only two copies — actually, one full edition and one damaged one — are known to have been preserved. The paper lasted until at least 1938, although it was converted to a monthly in late 1937.

As Kenniebrew’s health worsened, he gave up the medical practice in 1940 and died three years later.

After Dr. Kenniebrew’s death, Jessie Mae Schultz Kenniebrew married again to Theo Finley of Springfield. She founded the Voices of Love, Joy and Peace, was active in a variety of musical, civic and religious initiatives and was named Springfield’s First Citizenin 1976.

In 2008, the Sangamon County Medical Society formally apologized for refusing to accept Kenniebrew’s applications for membership in the 1920s and ‘30s.

More information: Charlotte Kenniebrew Johnson, daughter of Alonzo and Jessie Mae Kenniebrew Finley, compiled and privately printed an extensive family history, George Schultz and His, in 1995. A copy is available in the Sangamon Valley Collection at Lincoln Library, Springfield.

Original content copyright Sangamon County Historical Society. You are free to republish this content as long as credit is given to the Society.